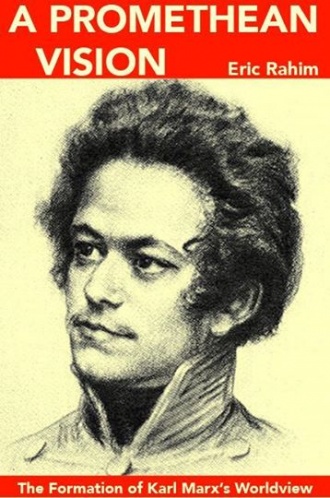

A Promethean Vision: The Formation of Marx’s World View

by Eric Rahim, Praxis Press.

ACCESSIBLE to the general reader, A Promethean Vision looks at the process by which Karl Marx, still in his late twenties, arrived at his revolutionary leap of understanding about how human society develops.

Writers before Marx had talked about stages, with some seeing them in economic terms — from hunting to agriculture to commerce and manufacture. A few had even talked about dominant classes.

But it was Marx who related classes to the specific way an economic surplus was extracted — exploitatively through a particular exercise of state power — with this in turn being related to the technological potential reached by humanity at that stage.

It was this world view that enabled Marx, along with Frederic Engels, to draft the Communist Manifesto in 1847 and assert that “the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

What then does Eric Rahim add to our understanding of how Marx developed this perspective?

He traces Marx’s intellectual development month by month, and sometimes week by week, from his schoolboy initiation into French enlightenment philosophy to his encounter with Hegel’s dialectics at university.

This was in its day a revolutionary philosophy because it stressed the continual transformation of human society through ideas.

Yet Marx reversed the sequence and argued that it was not ideas that drove change but humanity’s “material being” that continually transformed consciousness.

It was this new materialist understanding of dialectics that Marx then applied to the economics promulgated by Adam Smith and the English and Scottish writers who had first analysed Britain’s developing capitalist economy.

It was, Rahim argues, Marx’s ability to understand Smith dialectically, in terms of the material sequence of human development, that was critical.

It was this that enabled him to demonstrate that Smith’s trinity of capital, landownership and labour was not absolute, lasting for all time.

On the contrary, it depended on a particular structure of state power, maintained by a ruling class, which alone enabled capital to exploit labour and appropriate the surplus.

Labour power, Marx argued, only existed as such because it had been forcibly divorced from the means of subsistence on the land.

Land only existed as capitalist property because feudal power had been overthrown and it became capital because its exploitative accumulation was legally protected.

All depended, as Marx said, on the way classes and class struggle were bound up with particular historical phases in the development of production.

This itself, Marx stressed, was the outcome of the constant and ever-continuing process by which people, as intelligent and creative producers, interacted with and enhanced the material achievements of each previous generation.

Rahim’s book captures the excitement of Marx’s encounter with an Engels fresh from his investigation of English capitalism in 1844 and Marx’s resulting visit with Engels to Lancashire in 1845.

It was over the following two years that Marx worked his way through the writings of the British political economists and the result was his world view, first outlined in the Communist Manifesto.

Rahim’s work is relatively short and it takes the story no further than 1851. But it illuminates with great clarity the origins of the world view on which the subsequent development of Marx’s thought depended.

Can I pay by Cheque?